[ad_1]

If a trip to Christmas Island sounds like fun, you’d be wrong. This remote tropical island in the Indian Ocean, known as a birdwatcher’s paradise and a snorkeler’s haven, has a dark side. It’s home to 1,102 asylum-seeking detainees, including 174 children; many of them are infants, and 26 boys are unaccompanied minors.

Attempting to travel to Australia by boat and was intercepted after 19 July 2013 ( Changes in immigration policy), who were detained against their will in an Australian Immigration Detention Centreand promised to Never settled on the Australian mainland. After the first anniversary of the detention, tensions are rising.

I was invited to accompany Professor Gillian Triggs, Chair of the Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC), and her team to Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centre In July.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lkz_WYzZMa4

This visit was in 2014 National Survey of Children in Immigration Detention. This is caused by Reports of self-harm are increasing Mothers with young children.

Symptoms of mental and physical distress

As a pediatrician, my role is to interview children and families, visit their homes, and comment on the impact detention has had on their lives (health and mental health). Parents described their children as being “always sick.” Certainly, during our visits, most children were sick with respiratory viruses.

Young children are vulnerable to infection, and crowded living conditions on the islands facilitate the spread of infection within and between families. Many report persistent wheezing (asthma), which may be exacerbated by repeated infections and constant air conditioning. Some children have waited months to be transferred to the mainland for specialist treatment, including surgery.

However, what is most distressing is that emotions are running high.

We interviewed over 200 people, and two weeks later, their words are still haunting me.

“My life is really over,” wrote a 12-year-old girl who said she had been physically abused in her hometown and her mother had self-harmed in detention. She had not eaten or spoken for three days and had threatened to harm herself.

I don’t want to die because I know I can’t live here anymore after I die. If I go back to xxxxx I know they will kill me and my family.

Children with a tendency to self-harm are a cause for concern. Immigration Department data confirmed that 128 children had self-harmed. Self-harm in the “domestic” detention networkThis included Christmas Island and mainland detention centres from 1 January 2013 to 31 March 2014.

Many of the children we meet are anxious and show signs of post-traumatic stress disorder and current distress. We see children who describe intrusive flashbacks and nightmares, who begin to wet the bed or stutter, who refuse to eat and drink, and who stop talking.

Some people expressed their feelings through drawings. In the following drawing, a five-year-old girl whose mother had self-harmed described (from left to right):

It was just my mum crying, I was crying too because I had no friends and I didn’t like being on Christmas Island, and dad too.

Author provided

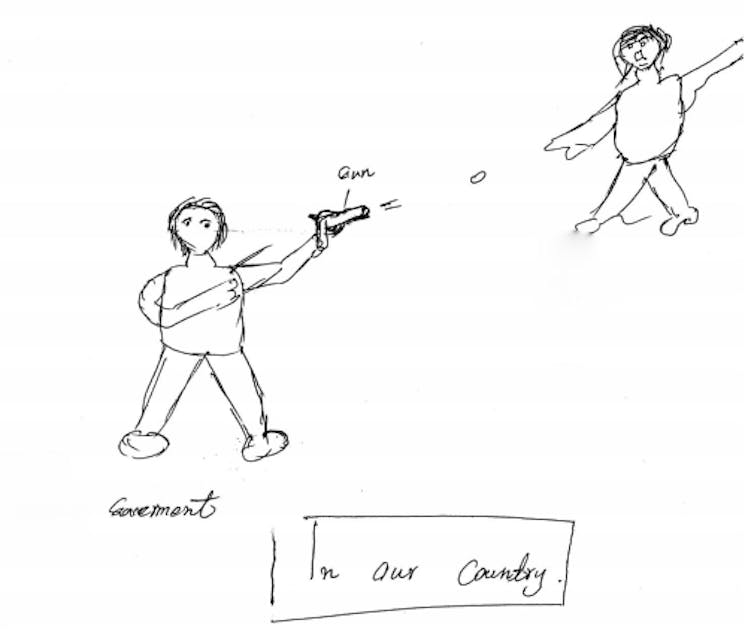

Children often describe distressing conditions in the countries they have fled (see the drawing below by a 16-year-old unaccompanied minor).

Author provided

Many described their situation as “hopeless” and claimed they “see no future”. One 17-year-old unaccompanied minor said:

We are very sad because I have been detained. Is there anyone in Australia who can help us? Please help us.

The suffering of the detainees was palpable during our visits. They expressed extreme sadness and helplessness, most notably in the prevalence of self-harm among young mothers and the psychological symptoms their children displayed.

Although this was my first visit to Christmas Island, colleagues who had been there before were struck by the change in mood, Triggs said. describe as “very serious deterioration”.

Only release can alleviate the damage

We did see some changes: a playground under construction, a playroom with toys (which is not yet in use and will be used on a limited basis due to the large number of children on the island), a shade cloth covering the play area, and a school that will soon open. Perhaps these improvements are too little, too late.

Mandatory child detention on Christmas Island No longer a humane choiceIt is time to move families with children and unaccompanied minors to Community detention On the mainland, they will have freedom of movement and can enjoy It’s their rightThese include specialized Health and Mental Health And education. We can’t keep these people in limbo any longer.

We have an obligation under international law to assess their refugee claims. Unless their refugee assessments are expedited, we will not curb rising rates of mental illness. Under international law, we cannot return them to the countries from which they fled persecution, and they must have some control over their fate, regardless of the outcome of the assessment.

Life without certainty—wherever that certainty might be—is unbearable.

[ad_2]

Source link