[ad_1]

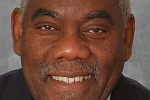

By Selwyn R. Cudjoe, Ph.D.

June 26, 2024

I first encountered Philip Henry Douglin while writing Beyond Borders: Intellectual Traditions in Nineteenth-Century Trinidad and Tobago (2003). Since then, I have been collecting information about Douglin in research centers such as the Watson Collection at Oxford University, the British Archives at Kew in London, and the Trinidad and Tobago Archives in Port of Spain. But I knew that before I could complete his biography, I had to go to Barbados.

I first encountered Philip Henry Douglin while writing Beyond Borders: Intellectual Traditions in Nineteenth-Century Trinidad and Tobago (2003). Since then, I have been collecting information about Douglin in research centers such as the Watson Collection at Oxford University, the British Archives at Kew in London, and the Trinidad and Tobago Archives in Port of Spain. But I knew that before I could complete his biography, I had to go to Barbados.

Douglin was born in 1845 in Scotland, Barbados, to slave parents. His mother loved the church, so he joined it. He attended a primary school that was built for slaves and their children. In 1862, he entered Codrington College, where he studied under the Rev. Richard Rawl, the headmaster of Codrington College and the first bishop of Trinidad. Rawl remained Douglin’s mentor throughout his life.

In 1867, after receiving ordination, the West Indian Church sent him as a missionary to Rio Pongas in West Africa, where he served for 19 years. In 1886, tired of the harsh climate of West Africa and repeated bouts of malaria, he came to Trinidad to serve as pastor of St. Madeleine and St. Clement’s Church. Bishop Rolle was responsible for bringing him here.

Douglin was also a social activist. He participated in the movement to free black slaves and in 1888 made the most in-depth analysis of the impact of slavery on the African psyche. In 1901, Williams came to Trinidad to establish a branch of the Pan-African Association, and Douglin became one of Williams’ main assistants. Douglin died in 1902.

In January I visited Codrington College to research Douglin’s early life further. Although I found some interesting information there, Dr. Noel Titus, former president of Codrington College, suggested that I go to the Barbados Archives to consult the Guide to the Records of the Barbados Manuscript Collection, where he said I might find more information about Douglin.

He cites in particular ‘Records of the West Indian Church Society for the Promotion of the Gospel at the Pongas Mission, 1850-1960, from the Bishop’s Court Parish Records Collection.’ The collection is a gold mine of information.

On June 5, I returned to the Barbados Archives to continue studying the collection. The archives contain minutes of meetings of the West Indian Church Association, correspondence with the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, extracts from letters written by missionaries to the Barbados headquarters, and records of their struggle to continue their missions. I spent my first week and a half there diligently studying the collection.

Imagine my dismay when I arrived at the archives on Tuesday morning to find it enveloped in smoke. There must have been eight fire engines parked there. The Mid-Week Nation reported the tragedy on its front page: “Senator Dr Shantal Munro-Knight, Minister in the Prime Minister’s Office responsible for Culture, visited the archives at Black Rock, St Michael yesterday morning and was visibly shocked when Block D was destroyed by fire. Fortunately, fire officials said the blaze was caused by a lightning strike late Monday night and was contained to that building.” (June 19).

Fortunately, the file I was working on survived because the archivist had taken it out of Block D and placed it on my desk every morning. Unfortunately, hundreds of years of records were lost in the fire.

Chief Archivist Ingrid Thompson spoke of the state of the records: “We were able to salvage some records, but most of them were destroyed. Some of those records included church records, city council records, medical (psychiatric) hospital records… Some of those documents we were unable to recover.”

The archives were closed from Tuesday to Friday, but a sympathetic archivist, Stacia Adams, felt sorry for me and, seeing my frustration, allowed me to view the Bishop’s Court Parish records on Thursday. I was the only member of the public allowed into the archives since Tuesday.

I have read most of the files, and it will take another day to read the entire record. Because they helped me take out these files, I was able to save at least one precious document from those that were burned or soaked in water.

Although I had been researching Douglin’s life for 20 years, something deep inside me – perhaps a writer’s instinct – told me that I would not be able to fully capture his life until I visited his homeland.

I never expected my search to end this way. It reminded me of the Trinidadian archives and the wisdom of our local proverb, “When your neighbor’s house is on fire, get your house wet,” and the imperative: “Digitize, digitize, digitize.”

[ad_2]

Source link