[ad_1]

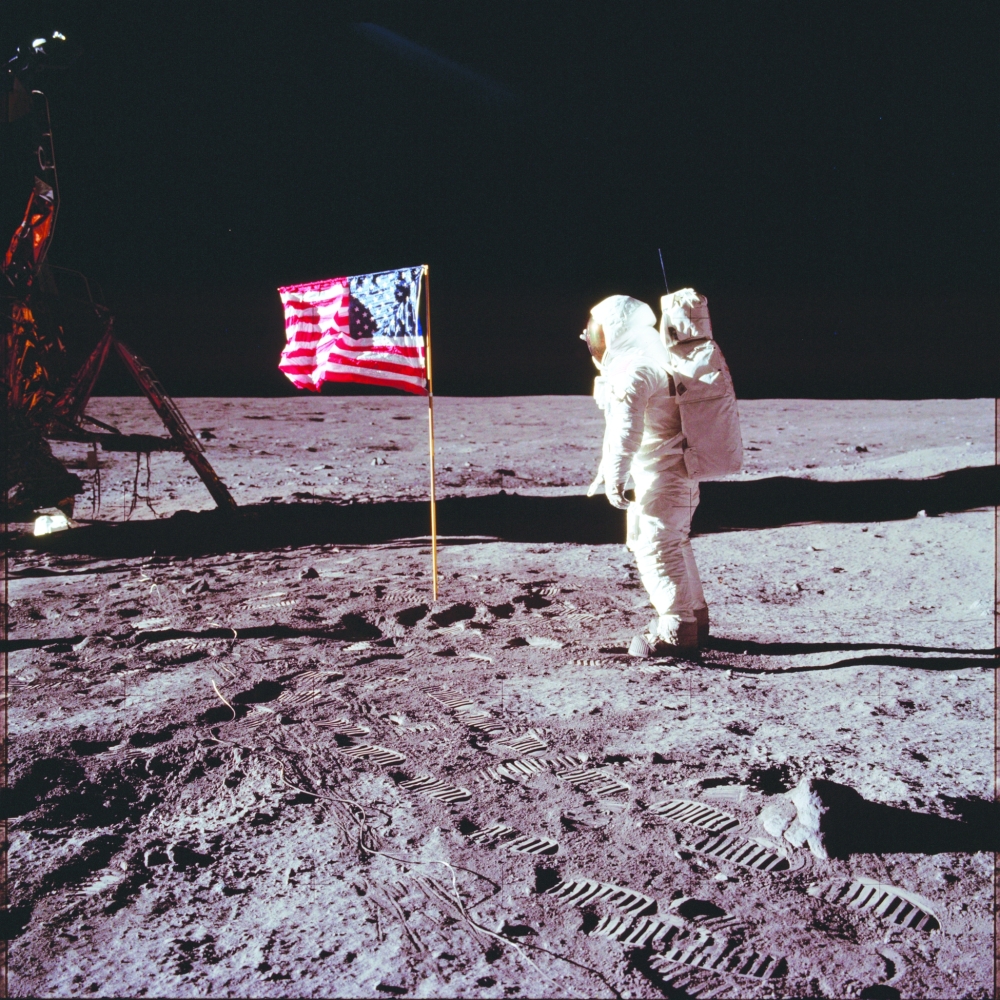

Scarlett Johansson and Channing Tatum’s new film Fly Me to the Moon uses a long-debunked conspiracy theory as its starting point to create a space race romantic comedy. In the late 1960s, a cautious NASA realizes it needs to improve its PR during the Vietnam War. The resulting publicity campaign leads to a fake Apollo 11 mission being filmed on a soundstage while the real mission unfolds. Pranks and romance ensue.

Fly Me to the Moon isn’t the first film to feature the idea that the moon landings were a hoax, with the conspiracy theory first appearing in the 1970s. Capricorn One (1978) featured a faked mission to Mars that exploited institutional mistrust during the Watergate era, while the more recent Moonwalkers (2015) had a CIA agent team up with a rock band manager to fake the Apollo 11 moon landing.

What makes Fly Me to the Moon special is its insistence on the truth. The film’s writers say they hope the film will reinforce the true story of the moon landing. But in the post-COVID-19 era, with conspiracy theories amplified on social media, is that possible?

The script, written by Rose Gilroy from a story by Keenan Flynn and Bill Kirstein, plays with that theory, including a joke about some conspiracy theorists’ allegations that director Stanley Kubrick faked the historical event. (He didn’t.) But ultimately, the film emphasizes that the Apollo 11 landing really did happen.

Flynn said that the original idea for the film came in 2016. It was during the US presidential election, and the whole country was arguing about the truth. Donald Trump frequently criticized the media for “lying” during the campaign, and the moon landing became the perfect background for the film.

“That’s the mission,” Flynn said. “How do you have your cake and eat it too? You pretend that the moon landing was fun, but you actually drive home the point of the truth by highlighting that achievement.”

Gilroy said she had read some books to get a better understanding of the conspiracy, but they were simply devoid of content.

“We wanted to build a story around the idea that these people came together to ensure the authenticity of the mission,” she said. “In all my research, I never found anything that made me question the authenticity of this achievement.”

Adam Frank, an astronomer and physicist at the University of Rochester whose work focuses on science denial, said popular culture has a responsibility to combat nihilistic tendencies toward doubting science and human potential.

“It’s lazy to say ‘the government was involved in a conspiracy’ instead of ‘people actually got together and found the answer,’ ” Frank said. “They worked for 20 years and sent a probe to Mars and it did exactly what they said it would do. Somehow that’s less exciting than ‘it didn’t work, they had a conspiracy.’ ”

Fly Me to the Moon does focus on the hard work that went into getting to the moon. But now more than ever, it’s easier to take images out of context and spread them online, and good intentions can fall flat. Concerns about the film might also be a little odd at this time: Earlier this year, AI-generated images of fake moon landing movie scenes went viral.

Lawrence Hamilton, a sociology professor at the University of New Hampshire who studies anti-science conspiracy theories, noted that moon landing deniers have used an image as a warning: an image showing astronauts without helmets during a training exercise at the Kennedy Space Center that has been shared many times on social media over the years.

“They said, ‘Here’s the proof that they faked the moon landing,’ ” he recalled. “They’re going to do the same thing with footage from this movie. They’re going to do whatever it takes to say, ‘This proves what we’ve been saying all along.’ ”

For those who don’t have strong memories of watching the moon landing, the impact can be huge. In a 2021 national survey, Hamilton found that only 12% of respondents believed the moon landing was faked, but millennials were more likely than other generations to deny it happened.

Gen Z is more likely to be unsure if it really happened. A recent TikTok filter that asks users to rank something on a scale of 1 to 10 based on how much they believe it, with 1 being more likely and 10 being less likely, inspired multiple videos in which people put the moon landing down to things like God, magic and ghosts. But a few viral videos don’t mean Gen Z is flocking to support moon landing conspiracy theories, the survey shows.

One person who isn’t concerned that the film might inadvertently fuel conspiracy theories is actress Ana Garcia, who plays Johnson’s character’s assistant, Ruby.

“I think if someone was really dumb, they would understand that,” Garcia told Variety at the film’s premiere. “I think if someone was dumb as a rock, they would say, ‘This is fake.’ ” — The New York Times

[ad_2]

Source link