[ad_1]

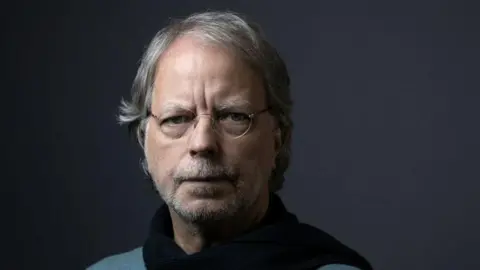

Getty Images

Getty ImagesInternationally renowned author and poet Mia Couto identifies himself as African, but his roots are in Europe.

His Portuguese parents settled in Mozambique in 1953 after fleeing the dictatorship of Antonio Salazar.

Two years later, Couto was born in the port city of Beira.

“I had a very happy childhood,” he told the BBC.

He noted that he was aware that he lived in a “colonial society” and that no one needed to explain this to him because “the boundaries between white and black, between poor and rich, were so clear.”

As a child, Kotto was extremely shy and unable to speak up for himself in public or even at home.

Instead, like his father, also a poet and journalist, he found solace in words.

“I invent something, I create a relationship with paper, and then behind that paper there is always someone I love, someone who listens to me and says to me: ‘You exist’,” he told the BBC at his home in Maputo, the capital of Mozambique, against a backdrop of a brightly coloured mustard yellow wall with a painting and some wood carvings.

Because of his European ancestry, Couto identified most readily with the black elite of Portuguese-colonial Mozambique, the “assimilated,” who, in the racist language of the time, were considered “civilized” enough to become Portuguese citizens.

The author considers himself lucky to have been able to play with the children of assimilated people and to learn some of their language.

He said it helped him fit in with the black majority.

“I only remember that I’m white when I’m outside Mozambique. Inside Mozambique, it doesn’t happen at all,” he said.

Yet, as a child, he recognized that his whiteness made him different.

“No one taught me what injustice was … how unfair the society I lived in was. I thought: ‘I can’t be myself. I can’t be a happy person if I don’t fight this,'” he said.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen Couto was ten years old, Mozambique’s rebellion against Portuguese rule began.

The author remembers one evening when, as a 17-year-old student, he was writing poetry for an anti-colonial publication and eager to join the liberation struggle when he was summoned before the leaders of the revolutionary movement, the Liberation Front.

Arriving at their dormitory, he found himself the only white boy among 30 people.

The leader asked everyone in the room to describe what they had suffered and why they wanted to join the liberation front.

Couto was the last to speak. As he heard the stories of poverty and deprivation, he realized he was the only privileged person in the room.

So he made up a story about himself—otherwise he knew he had no chance of being chosen.

“But when it was my turn, I was speechless and I was overwhelmed with emotion,” he said.

What saved him was that Frelimo leaders had discovered his poetry and thought he could help their cause.

“The guy running the meeting asked me: ‘Are you the young guy who writes poetry in the newspaper?’ I said: ‘Yes, I am the author.’ He said: ‘OK, you can come, you can be one of us, because we need poetry,’ ” Coto recalled.

After Mozambique gained independence from Portugal in 1975, Couto continued to work as a journalist for local media until the death of Mozambique’s first president, Samora Machel, in 1986. He resigned due to disillusionment with the Mozambique Liberation Front.

“There is a break; I no longer believe what the liberators say,” he said.

After leaving FRELIMO, Couto studied biological sciences and today he is an ecologist specializing in coastal areas.

He also started writing again.

“I started out writing poetry, then books, short stories and novels,” he said.

His first novel, Sleepwalking, was published in 1992.

This is a magical realist fantasy novel inspired by Mozambique’s post-independence civil war, taking readers through the brutal conflict between the National Resistance of Mozambique (then a rebel group backed by South Africa’s white minority regime and Western powers) and the Frelimo forces from 1977 to 1992.

The book was an immediate success. In 2001, judges at the Zimbabwe International Book Fair named it one of the 12 best African books of the 20th century, and it has been translated into more than 33 languages.

Couto later gained recognition for more novels and short stories about war and colonialism, the pain and suffering experienced by Mozambicans, and their resilience in difficult times.

Other themes he focuses on include mysterious descriptions derived from witchcraft, religion, and folklore.

“I want a language that can translate the relationships and dialogues between the different dimensions within Africa, between the living and the dead, between the visible and the invisible,” he told the BBC.

Couto is well-known throughout the Portuguese-speaking world, including in Angola, Cape Verde and Sao Tome in Africa, as well as in Brazil and Portugal.

In 2013 he won the €100,000 ($109,000; £85,500) Camões Prize, the highest award for a Portuguese writer.

In 2014 he was awarded the $50,000 (£39,000) Neustadt Prize for Literature, considered the most prestigious literary award after the Nobel Prize.

When asked if his work reflects the reality of Africa today, Couto responded that it is impossible because the continent is divided and there are many different Africas.

“Because of the boundaries of colonial languages like French, English and Portuguese, we don’t know each other, and we don’t publish the works of our own writers on the continent,” he said.

He added: “We have inherited some colonial architecture that has now been ‘naturalised’, which is what is called English Africa, French Africa and Portuguese Africa.”

Kotto was supposed to travel to Kenya last month to attend a literary festival, but was unfortunately forced to cancel the trip due to massive protests over comments made by President William Ruto. Raising taxes.

He hopes there will be other opportunities to strengthen ties with writers in other parts of Africa.

“We need to break down these barriers. We need to place more emphasis on our engagement as Africans and among Africans,” Couto said.

He lamented that African writers constantly used Europe and America as reference points, but were shy about celebrating their own diversity and relationships with their gods and ancestors.

“In fact, we don’t even know what is happening in the arts and culture sector outside of Mozambique. Our neighbours – South Africa, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Tanzania – we know nothing about them and they know nothing about Mozambique,” Couto said.

When asked what advice he would give to young writers just starting out, he stressed the need to listen to other voices.

“Listening is more than just hearing a voice, looking at an iPhone or other gadget or tablet. It’s more about being able to be someone else. It’s a transference, an invisible transference of being someone else,” Coto said.

“If you are moved by a character in a book, it is because that character already lives deep inside you without you knowing it.”

You may also be interested in:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC[ad_2]

Source link