[ad_1]

66 million years ago, a giant asteroid impacted the Earth, greatly affecting the marine and terrestrial environments and causing the extinction of many animal and plant species. Among the species that survived the impact were the highly adaptable crocodilian reptiles. To determine the diet and habitat of these ancient species, the team from the LGL-TPE laboratory in Lyon (southeast France)* used a variety of methods, including chemical analysis of their bones and detailed studies of their skulls.

*The Lyon Geological Laboratory: Earth, Planets, Environment (LGL-TPE) is a unit of CNRS/ENS Lyon/Université Claude Bernard.

This research was funded in whole or in part by the French National Research Agency (ANR) under the project ANR SEBEK – AAPG2019. This report was prepared and funded as part of the “Science and Society – Scientific Technology and Industrial Culture” (SAPS) call for projects.

Artist’s impression of “Dentaneosuchus crassiproratus”. “D. crassiproratus” was 3 to 4 meters long and had teeth capable of tearing prey apart, making it a carnivorous terrestrial predator, unlike crocodiles that were adapted to a semi-aquatic life. It belonged to the Sebecosuchia group, a name derived from the Egyptian crocodile god Sobek, and it appears to have lived in a subtropical forest environment in southern France, about 45 million years ago, during the Eocene period.

Image by Donatelle LIENS / LGL-TPE / CNRS

Finding fossils is a skill that requires keen observation and a lot of patience. The paleontologist from the Lyon Geological Laboratory has just found a fossilized crocodile skull, part of the joint between the skull and the jaw, at an excavation site in Minervois (southern France). The fossil was photographed and measured, then carefully removed.

Photo by Jeremy Martin/LGL-TPE/CNRS

To separate the fossils from the rock matrix, scientists use various methods, depending on the nature of the matrix. Here, the bones are preserved in a limestone composed of carbonates, and then removed using dilute acid, which dissolves the rock and gradually exposes the bones without damaging the phosphates contained in it. The stone is then washed with water. This stage can last for months, as the acid used is very dilute.

Photo by Simone Bianchetti/LGL-TPE/CNRS

Before a new round of acid treatment, the most vulnerable parts need to be protected with a hardener, which in most cases takes the form of a polymer adhesive. The hardener is carefully applied to fill any cracks, thus protecting the fossil and ensuring its cohesion. It can be removed if necessary.

Photo by Simone Bianchetti/LGL-TPE/CNRS

After several acid treatments, the surface of the crocodile bone fossil will undergo a final stage of mechanical removal, using micro-air abrasion and precision tools. At the end of this process, the fossil finally begins to reveal its secrets.

Photo by Simone Bianchetti/LGL-TPE/CNRS

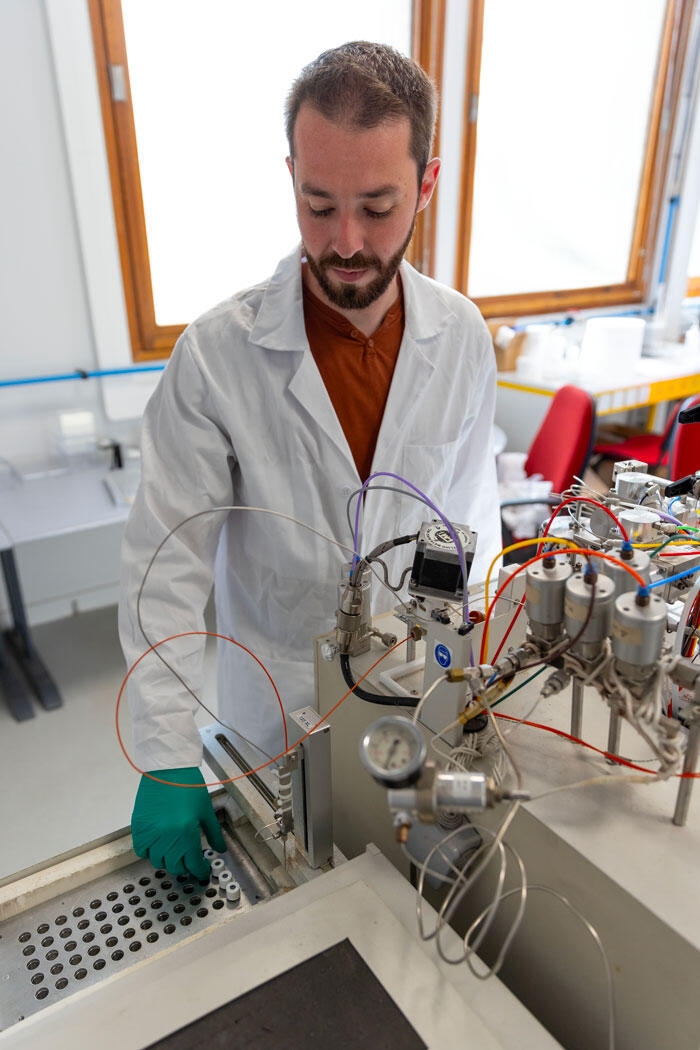

To understand what kind of environment D. crassiproratus lived in and what it ate, researchers are using a micro drill under a binocular magnifier to remove tooth enamel from the fossil teeth. Once the teeth are ground into a powder, they can begin various geochemical analyses.

Photo by Simone Bianchetti/LGL-TPE/CNRS

Throughout its life, Pachyspondylus accumulated one of the natural isotopes of carbon, ¹³C, in its tooth enamel. Isotopic analysis of the ratio between ¹³C and ¹²C, the most common isotope of carbon, in the fossil remains strongly suggests that Pachyspondylus was a “super predator” that probably fed on land mammals.

Photo by Simone Bianchetti/LGL-TPE/CNRS

The fossil remains were placed in silver capsules, still in powder form, and also analyzed by pyrolysis. Here, chemical analysis of oxygen isotopes (¹⁶O and ¹⁸O) provided information about the thermal physiology of the animal, indicating that it was most likely a purely terrestrial animal, like other Sebeckian crocodilians.

Photo by Simone Bianchetti/LGL-TPE/CNRS

Fossils are usually found in small numbers and are therefore almost never complete. Therefore, in order to study the development of terrestrialism in crocodiles, in other words, their adaptation to a terrestrial lifestyle, paleontologists use the remains of specimens of contemporary species such as “Crocodylus siamensis” as reference data. Here, the skull was scanned with a structured light surface scanner. This was used to generate a 3D model of the entire skull surface.

Photo by Simone Bianchetti/LGL-TPE/CNRS

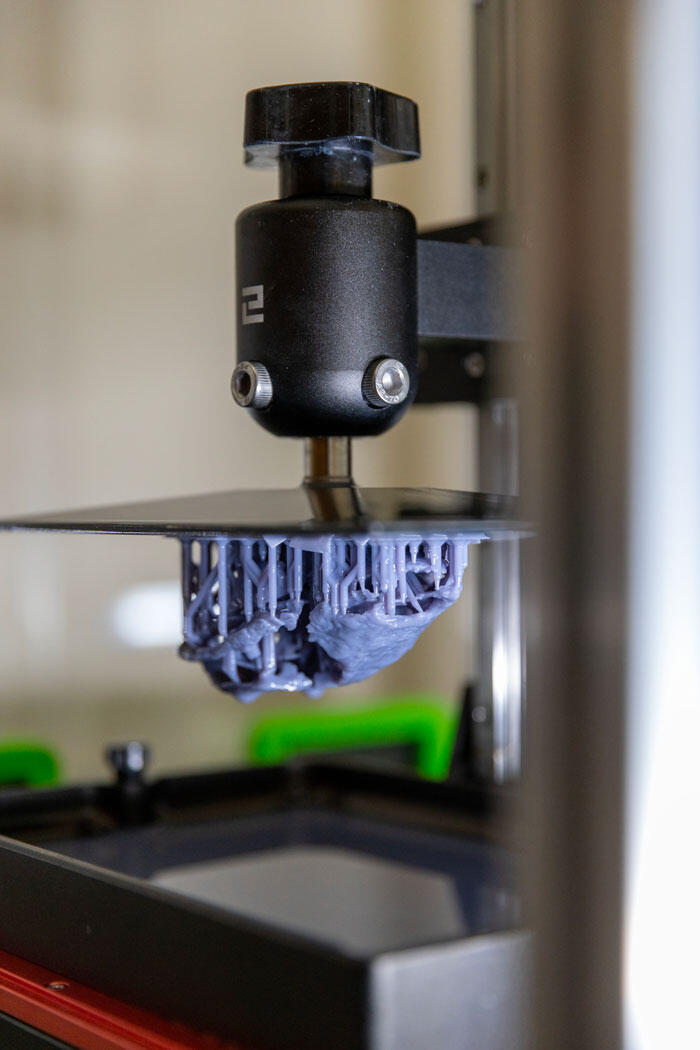

Using various scanning methods, the researchers 3D printed the skull of the “Arambourgia gaudryi,” an extinct semi-terrestrial crocodile closely related to today’s crocodiles, in liquid resin. At the end of the process, the resin was cured by exposure to ultraviolet light.

Photo by Simone Bianchetti/LGL-TPE/CNRS

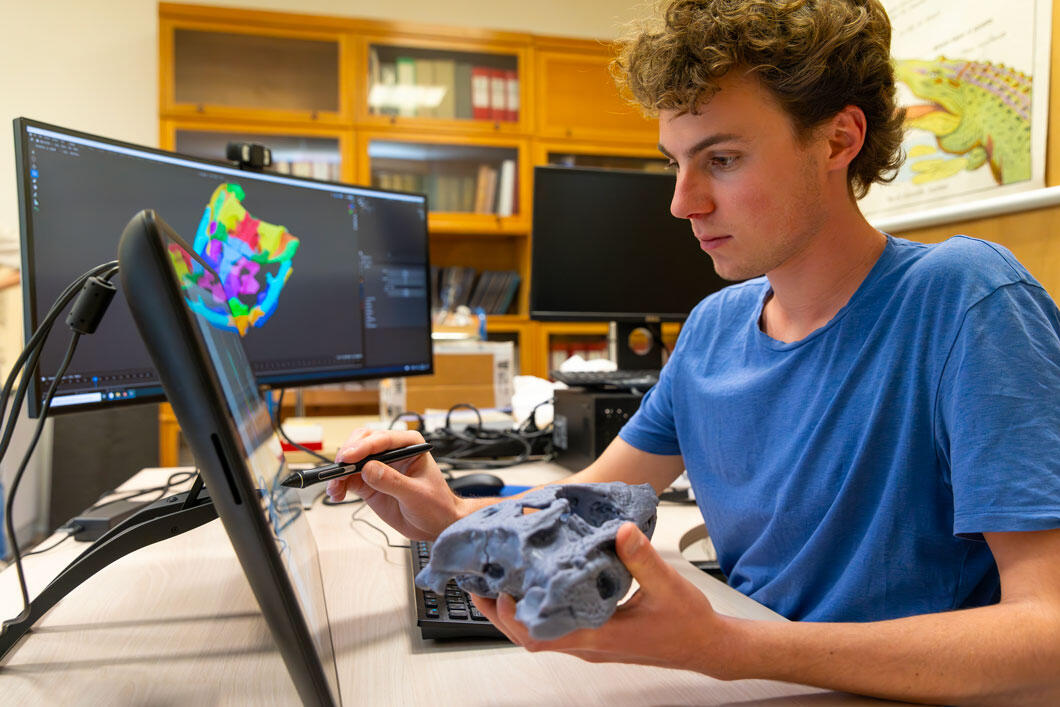

Each bone in the Arambourgia gaudryi skull is identified with a specific color. This serves as a guide for the distribution of bones on the resin 3D print, providing a tactile and visual representation of this extinct species.

Photo by Simone Bianchetti/LGL-TPE/CNRS

Fossils, like this crocodile jawbone, are boxed and collected by museums and universities. This allows paleontologists to build an archive that other researchers can review, while also documenting any handling the fossil may have undergone. To ensure preservation, the fossils are kept in constant humidity and temperature conditions.

Photo by Simone Bianchetti/LGL-TPE/CNRS

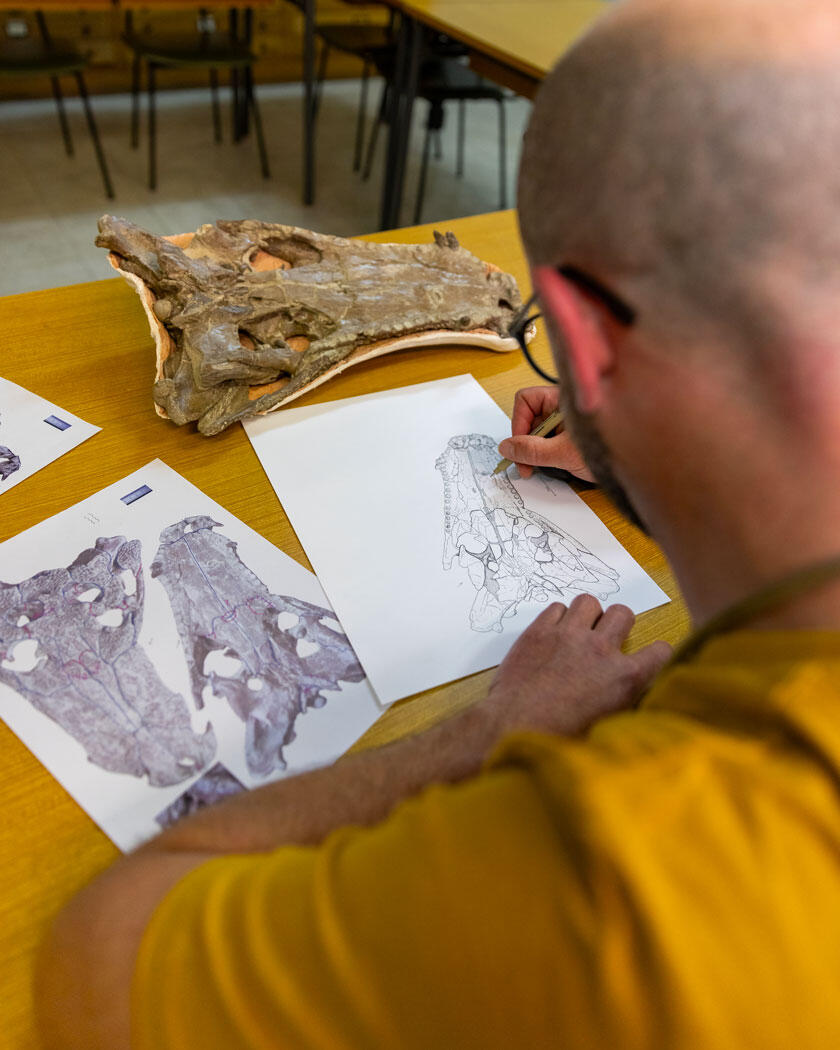

Another tool paleontologists use is fossil interpretive drawings. These drawings are usually based on fossil remains, photographs, and sometimes three-dimensional models of the specimens, and are drawn by the scientists themselves. They are used to illustrate specimens presented in scientific papers or to help explain findings to non-experts.

Photo by Simone Bianchetti/LGL-TPE/CNRS

[ad_2]

Source link