[ad_1]

Forests cover one third of the world’s land surface. Despite the invaluable services they provide us, they are now under so much pressure that we are confronted with their sometimes conflicting roles – both as a refuge for biodiversity and as a source of (over)logged material.

(This article is extracted from the archives “Forests are treasures worth protecting” (“Forests, a treasure to be protected”), originally published in issue 16 of the magazine (in French) Science Notebook).

Will our forests disappear? The 2023 megafires were so fierce and so untimely that they highlighted the fragility of the world’s woodlands. Alberta in western Canada was engulfed in fire in early spring. 3,500 km2) was reduced to ashes in less than a week, and 30,000 people were forced to evacuate. Meanwhile, in Russia, 6,000 km2 In May, boreal forests in the Ural Mountains and Siberia burned. Spain, Greece and the entire Mediterranean basin were also affected, while already in April, record fires broke out in the Pyrénées-Orientales department in southwestern France.

“You have to be very careful when analyzing wildfires.” Professor Emeritus of Geography, Social Sciences, Panthéon-Sorbonne University, Paris Dynamics and Reorganization of Space LiftLaboratory (LADYSS). “Globally, the area of forest fires has not increased much over the past thirty years, with 3 to 4 million square kilometers burned every year, according to satellite data from the Copernicus program. On the other hand, the nature of the fires has completely changed. In the past there were many small fires. But now we are facing very large and absolutely devastating fires.

A massive wildfire in British Columbia, Canada.

These megafires, which first appeared about 15 years ago, are driven by global warming and drought in forest areas. But those are not the only factors.”In California and Australia, for example, fires often start at the interface between urban areas and woodlands, because the closer a home is to a forest, the greater the risk of fire. In Russia, the 2023 drought was exacerbated by the dismissal of half of the forest rangers. Fires have plenty of time to spread before they are detected, ” Simon pointed out.

What exactly is a forest?

Regardless, the fires have taught us one thing: forests are complex objects that defy simple description. In fact, simply defining them is quite difficult. What exactly is a forest? Can a savanna with very uneven tree cover or a so-called “urban microforest” at the end of a street really be called a forest? “Today, the definition proposed by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) is the most widely used internationally.” Simon explained. “The law stipulates that forests must cover at least 10% of the land surface, have an area of at least half a hectare, and have mature trees of at least 5 meters in height.”

This is a rather broad description that was reached as a result of international compromise, especially for negotiations on carbon emission quotas and national contributions to reducing greenhouse gases (forests are an efficient natural carbon sink). However, not all scientists are satisfied with this, and ecologists are the first to believe that forests are not only composed of tree cover, but also complex ecosystems. “A half-hectare patch of trees has far less biodiversity than a large forest and does not constitute a fully functioning ecosystem.” said Philippe Grandcolas, deputy scientific director of the Ecology and Environment Department at the French National Center for Scientific Research.

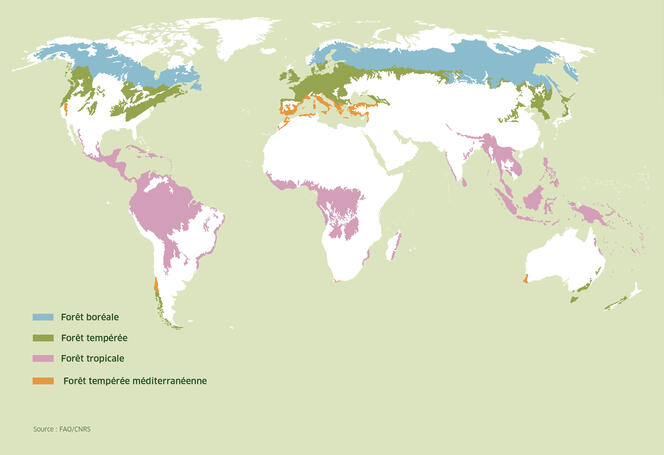

Leaving these debates aside, forests currently cover 30% of the Earth’s surface, or about 44 million square kilometers, according to the FAO definition. Forests can be divided into four main types. In the far north, boreal forests are vast coniferous forests that extend from Russia to Canada and Scandinavia, accounting for a little over a third of the world’s forest area. Tropical forests, located on both sides of the equator, have hundreds of deciduous and evergreen tree species and account for nearly a third of the world’s forest area, but have by far the largest forest biomass and are the most ecologically complex. Next are temperate woodlands, mainly in Europe and the United States, where a mixture of deciduous trees and conifers grow. Finally, there are Mediterranean forests, whose vegetation is sclerophyllous and are found not only around the Mediterranean, but also in southern California, the Cape region of South Africa, and around Valparaiso, Chile.

Four major forest types. The boreal forests of Russia and Canada and the tropical rainforests of the Amazon, Congo Basin, and Indonesia make up the world’s largest forest areas.

These four types of forests differ not only in their overall appearance, but also in the way they function. “Both boreal and temperate forests are controlled by cold: during winter (which is longer in boreal forests), trees rest and stop photosynthesising. Mediterranean forests, on the contrary, rely on heat and, above all, water stress: during the worst of summer droughts, trees stop breathing to avoid losing water and noticeably reduce their plant activity,” Simon explains. Tropical rainforests, on the other hand, thrive year-round, have no discernible seasonal rhythm, and are always green.

Blamed for massive deforestation

While natural woodlands form complex ecosystems, many forests are often extremely simplified, often reduced to simple “woods” – rows of trees of the same species and age. This is due to certain types of forestry practices that prioritize simple management, using fast-growing conifers (which burn more easily) that are all planted and, therefore, felled at the same time. This approach is known as clearcutting, where all the trees in a large area are removed, leaving the ground completely bare.

However, “As the world warms, these standardized forests become barren ecosystems that lack resilience,” says Guillaume Decocq, a botanist at the EDYSAN laboratory. “They are less resilient to drought, storms and fire, and more susceptible to pathogens and pests.” Simply put, our forests are in trouble, constantly impacted by megafires and storms, fragmented by deforestation and by roads, highways and railways that cut through them. Yet they are vital because of the many services they provide.

In November 2023, a demonstration was held against the felling of 17 hectares of forest in Montagne de Lure (southeast France), where a photovoltaic plant was to be built.

Forests are the second largest natural carbon sink after the oceans, contribute to the global climate balance and are home to 80% of the planet’s biodiversity. They provide millions of people with wood for construction, heating and cooking and may soon become a source of biofuel for future aircraft. With half of the world’s population now living in cities, forests have become very popular places for recreation.

Conflicting expectations

“Today people have considerable and often conflicting expectations of forests,” Simon pointed out. “We want these places to have rich and thriving biodiversity and for nature to be preserved, but we also want them to provide us with more and more bio-based materials for the energy transition. We also want to be able to go hiking or mountain biking there.” Not surprisingly, usage conflicts are on the rise. “In France, where two-thirds of forests are privately owned, disputes between forest owners, loggers and the public are becoming more frequent, especially over deforestation, which is becoming less and less acceptable.” Decocq added.

So who really owns the forest? This is a key question, the botanist says, pointing to recent developments in French legislation on the issue.From now on, anyone entering private woodland, even unfenced, will be fined. In early 2024, in the Vosges Mountains (northeast France), the new owner of a forest crossed by several hiking trails announced that he would ban access to the forest to everyone. ”

Mountain biking in the Nord-Vosges Regional Natural Park in northeastern France.

Are forests part of the global heritage of humanity and all living things? How can we balance our different needs? “New forestry practices that are more compatible with forest ecosystems are beginning to emerge.” Simon said he still believes forests can coexist with humans. “Forests have been impacted by humans for thousands of years.” Geographers point out. “In the Middle Ages, the forests of Europe were anything but wilderness. Even today, the Amazon rainforest is often mistaken for a pristine wilderness, a product of thousands of years of human activity.” ♦

[ad_2]

Source link