[ad_1]

Cairo: The Gulf

She recommended her son More to them in a letter to her brothers, saying: “Take good care of my dear More, his health is very fragile and I cannot forgive him. Never abandon him, I would be crazy with joy if he lived with you.”

These were the last words written by the Russian poet Marina Tsvetaeva (1890-1930) before she selected a rope to pack her belongings and neighbors returned to see her hanged, her feet barely touching the ground.

A handful of neighbors carried Marina’s body to her final resting place, and no one said goodbye. No newspapers published the news of her death, and her name and date of birth were not engraved on the tombstone. There was no stone, wood or sign left, except for the books, manuscripts and diaries she left behind.

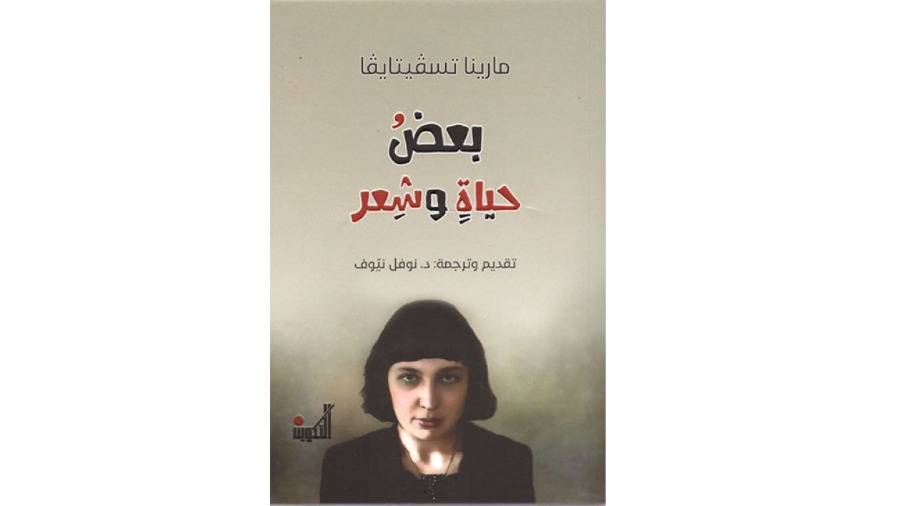

The book “Marina Tsvetaeva … reveals some of her life and poetry”, translated and presented by Dr. Tsvetaeva. Nofar Nayov said that Marina was not interested in anything except reading and reciting poems, everything flowed in her body with rhythm and music, she tended to the left since the Russian Revolution in 1905, and in the spring of 1907, the school summoned her father to take his daughter, so her father transferred her to a regular school.

She published her first collection of poetry, Evening Album, in complete secrecy when she was seventeen, during her penultimate year of high school, and published positive articles about it.

One critic harshly criticized Marina’s second collection, writing that “the atmosphere of the poems exudes a very putrid smell,” while another concluded that Marina “does not seek her own art form in her second collection. The poetic ability is strong, but she has her special subject, her private world between childhood and adolescence, her personal characteristics, her name, and it would be boring to read her second collection of poems about her mother and her colleagues.

The most significant turning point in the life of Marina, her family and her native Russia was the announcement of the start of World War I on July 16, 1914, which Marina initially adopted a hostile and indifferent attitude, but on the night of July 16, 1914, the Communists occupied the Winter Palace, the headquarters of the Provisional Government, and arrested the ministers, marking the beginning of a new era and a turning point in the history of Russia and the world as a whole.

Marina believed that the Tsar was responsible for what happened, but she made the Tsar cry and asked to spare him and his family from prison. Her husband served in the army as a military nurse during the war, and then he was released. At the end of 1917, he was called up and joined the Officer Academy, fought against the Communists and joined the White Army, and always remained loyal to the Tsarist regime.

In early 1921, Marina finished her collection of poems, The Swan Battalion, an ode to the White Army that she wrote from the beginning of the Communist Revolution to the end of the Civil War, and soon Pasternak suddenly struck the tune. One evening, she delivered a letter from Ehrenburg informing her that her husband was in Prague.

From that point on, her only concern was living with her husband in the worst and most dangerous conditions, in which case it was strange for Marina to be able to travel with her and her son.

Marina braved poverty in Prague, despite the harsh living conditions that consumed her time and strained her nerves. At this time, she attempted to publish her memoirs about the revolution she experienced in Moscow, but fear of the Soviet reaction caused the publisher to refuse to fulfill her wishes.

Ironically, the charges of treason and dalliance with Soviet agents brought against her and her husband, combined with the family’s poverty and poor living conditions, prompted the couple to consider moving to Paris in 1925, where refugee life became so depressing that in late 1926 she received a disappointing letter from the editorial board of the journal Modern Writing, which she had been publishing in Prague, asking her to return to writing clear poetry and to stop playing with complex styles.

No media platform refuses to deal with her, her poverty has reached the point of expulsion from France, forcing her to move between miserable, cheap and cold apartments, her home without tea and food. As she is going to a necessary meeting because her only shoe is no longer suitable for going out, her disappointment is multifaceted.

She realized she had to return to Russia because she had no money, could not publish, and was met with hostility and distrust everywhere, so she ended her 17-year exile and returned to Leningrad, where she suffered the same loneliness again, but in a more severe and cruel environment.

Marina began selecting a batch of poems that met the criteria for publication, with an internal “reading committee” that evaluated the manuscripts from a technical point of view and then considered their intellectual suitability for the readers who were building socialism. In a report on Marina’s poetry manuscripts, the first official to receive authoritative approval wrote: “The poet’s hostility to the Soviet regime and the extremely poor quality and ambiguity of her poems themselves are contrary to communist aesthetics.” Marina Tsvetaeva was given the task of printing a collection of her poems.

In 1950, the Soviet Writers’ Union recognized Marina as a great poet.

[ad_2]

Source link