[ad_1]

Many cellular phenomena are guided by mechanical forces, such as embryonic development or metastatic spread. These phenomena are the subject of intensive research aimed at understanding how they translate into biological processes. Of particular interest are new opportunities for the treatment of drug-resistant diseases such as cancer or fibrosis.

After a cut or scrape, the integrity of the skin is disrupted and the body must initiate a series of processes to start healing. To do this, cells need to migrate, shuttle, make contact and proliferate until they fill the space lost in the skin. These cell movements require the intervention of necessary mechanical actions. These phenomena have long been obscured by the millions of chemical reactions that drive the complex mechanisms of the human body, but they play a vital role in the biological world. Their study, known as mechanobiology, is now benefiting from numerous technological advances, especially microscopy.

“When scientists began studying cell imaging and embryology in the early 20th century,day century, they already believed that geometry and mechanics played an important role in cell physiology, division and migration.” Nicolas Minc, CNRS research professor at the Jacques Monod Institute, explains. “But with the discovery of DNA in 1953 and the widespread availability of genetic methods, these ideas were shelved for decades. It wasn’t until the late 1990s, with numerous advances in microscopy, that mechanical signals sensed by cells were once again considered.”

From Splitting to Migration

In fact, the precision of microscopes has been greatly developed, and now they can “see” inside tissues through a thickness of several micrometers. Some microscopes, such as the atomic force microscope (AFM), are equipped with probes that can measure the stiffness of cell membranes or specific components of cells. Traction force microscopy (TFM) can assess the forces exerted by a moving cell on its surroundings. All of these tools make it possible to study movements and forces within cells and, surprisingly, they can not only detect mechanical signals but also generate them. Therefore, entire aspects of biological functioning remain to be studied.

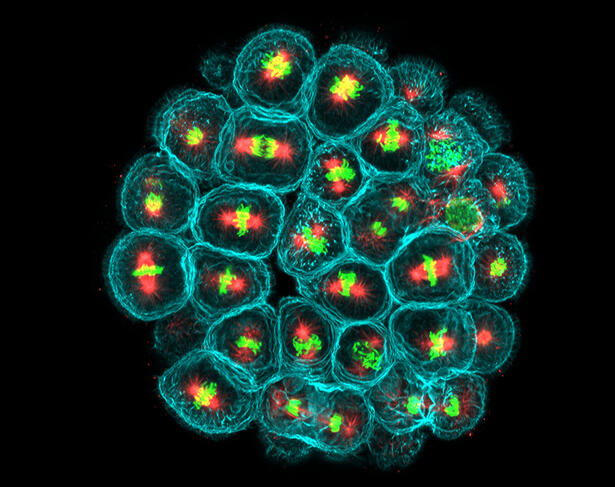

Microscopic image of a sea urchin embryo after 5 hours of development. Within each cell (with a turquoise membrane), the microtubules of the mitotic spindle (red) drive the chromosomes (green) in opposite directions to form two new cells.

For the past decade or so, Mink has been studying the effects of mechanical forces on cell geometry and division in sea urchin embryos. Sea urchins are animals that produce gametes (male or female reproductive cells) in large numbers. Like all eukaryotic cells that have a nucleus, cells in sea urchin embryos contain large numbers of fibers, or microtubules, that assemble into a network, the mitotic spindle. During the development of this network, genetic material is divided equally between mother and daughter cells. Mink and his team designed an original system in which they attached tiny magnetic beads to the mitotic spindles to control their position in the cell and measure the forces at work.

“We knew that fibers exert pressure inside cells, but we didn’t understand why it was important,” Minc explained.Our invention means that for the first time we can measure this pressure. The data obtained can be used to build a model of force generation at the scale of hundreds of thousands of microtubules.” The patented system indeed enables different mechanobiological studies, such as mechanotransduction, the phenomenon by which cells (mainly thanks to receptors on their surface) detect external mechanical forces and constraints and ultimately transform them into biochemical and genetic signals. These forces may come not only from the environment but also from nearby cells.

“This makes it possible to deliver information in a linear fashion.” Scientists introduced in detail. “For example, these signaling cascades can guide cell migration and other collective behaviors.” The researchers at the Institut Jacques Monod are also applying their magnetic system to the study of organoids, which are miniature artificial organs developed for humans.in vitro Looking at different pathologies, this work has really allowed us to gain a clearer understanding of how bowel cancer affects cell division and migration.

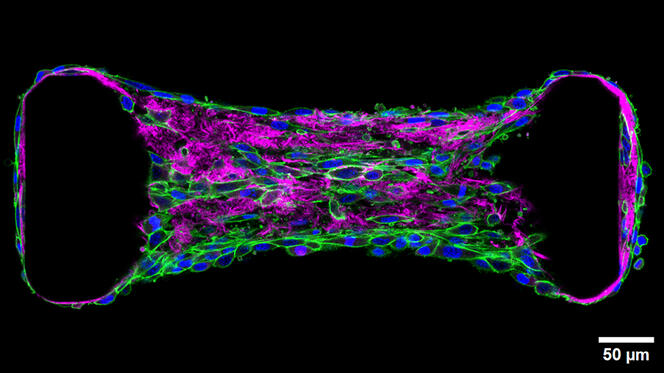

A 3D confocal microscopy image of a tissue created in the lab. It consists of photoactivated fibroblasts (green and blue) within a collagen matrix (pink) and spreading between two micropillars (two black clumps) that are susceptible to traction forces.

Migration occurs primarily in, on and through the extracellular matrix (ECM). The ECM is a macromolecular scaffold composed mainly of collagen synthesized and constructed by specialized cells (fibroblasts). As the site of the highest volume of cellular traffic, the ECM is currently a particular focus for scientists such as Thomas Boudou of the Interdisciplinary Laboratory of Physics (LIPhy), who is exploring the mechanobiology of tissues. “These cells exert a constant force on their surroundings and neighbors,” He explained. “The extracellular matrix can be likened to a spider’s web that allows mechanical signals to propagate along the fibers. This information can drive cell migration or differentiation.”

To study the mechanical forces involved in cell migration or differentiation, scientists use optogenetics: a method that enables the activation of specific proteins by light after genetic modification. Like a waterfall, this activation triggers another activation, which ultimately leads to the biological process of interest. Boudou thus turns cells into real levers that he can contract at will to observe how these movements affect the tissue and how far the signals can propagate. “Our approach is based on physiological responses,” He elaborated. “Because it is the cells that are exerting the force, the signaling remains within the realm of physiological reality.”

The study focused on fibrosis, the hardening and loss of elasticity of tissues following disease or inflammation. During this tissue change, fibroblasts somehow reactivate and produce excess collagen. This reactivation causes the cells to exert greater stress on their environment, inducing the activation of their immediate neighbors, setting off a vicious cycle and spreading fibrosis to all tissues.

Precursor mechanical force

How cells exert forces and influence each other is also at the heart of Jean-Léon Maître’s work. As a research professor in the Genetics and Developmental Biology department at the French National Center for Scientific Research, he is studying the development of mammalian embryos, focusing on humans and mice. “While cell chemistry is important, changes in embryo shape are primarily due to mechanical forces.” He explained. “These stimuli can also be converted into chemical reactions, which then induce gene expression.”

Maître used fluorescent markers to observe how cells stick to each other and how they exert pressure by contracting proteins on the cell surface. The scientists also used micropipettes to measure the force required to deform the cell surface and laser-guided optical tweezers to explore the mechanisms inside cells.

“We were able to see that the forces and cells involved change over time during mammalian embryonic development. The cells with the greatest pulling forces are located in the interior of the embryo. When the embryo contained only 16 cells, their position determined which cells would remain inside the embryo and which would form the placenta. This separation has long been studied by focusing on chemical criteria, but in fact, mechanical forces act upstream of changes in gene expression.”

Optical section of a human blastocyst, with the inner mass of cells that will give rise to all the cells of the body visible at the top. The actin cytoskeleton is shown in red/orange and the nuclear membrane in blue. The cavity in the center represents the lumen, the sac of fluid within the embryo.

The action of these forces begins inside the embryo at the eight-cell stage, just a few hours after fertilization. After an asymmetric division, the strongest daughter cells manage to drag themselves inside the cell mass, thus ensuring that they participate in the embryo rather than the placenta. Embryogenesis continues, and a fluid sac (lumen) forms inside the embryo, in which hydrostatic pressure breaks down the contact points between cells, causing fluid to accumulate where there is least adhesion between cells. Contractions around the cavity also cause the lumen to move, like air in a half-inflated balloon. “By changing the adhesiveness and contractility of the cells, you can control where the embryo attaches.” The master emphasized. “These findings may help improve fertility.”

A new approach: thermodynamics

Yves Rémond has a long-term vision for the therapeutic opportunities offered by mechanobiology. Professor Emeritus at the University of Strasbourg and ECPM European School of Chemistry, Polymers and Materials, and member of the ICube laboratory, has dedicated his life to studying the mechanical properties of composite materials and polymers, increasingly including biomaterials in this mix.Whether the material is inert or active, the physical and mechanical principles are the same.” Rémond and Rachele Allena, a lecturer at the University of Côte d’Azur in France and a member of Jean-Alexandre Dieudonné’s laboratory, developed the concept of therapeutic mechanics: treatments designed around the evolution of the mechanical properties of cells, tissues, bones and organs.

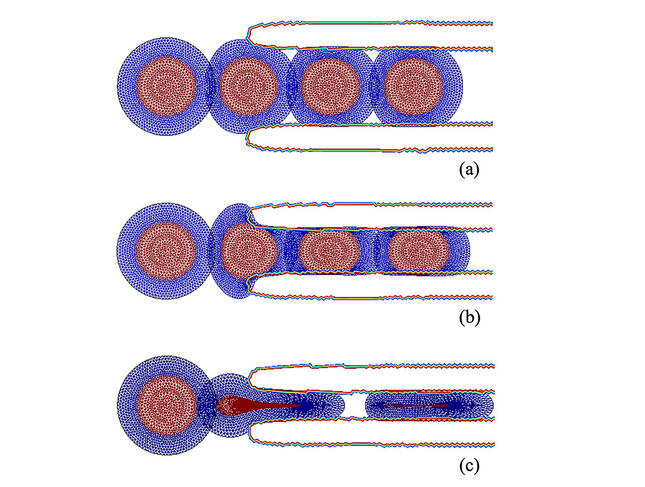

“The spread of cancer cells is primarily due to two major, deleterious mechanical effects,” Details Raymond. “They form metastases as they move, and their speed and direction vary depending on the stiffness of the biological surfaces, such as tissues, they encounter. When cancer cells metastasize from one tissue to another, they need to find ways into highly confined spaces, so they have to change shape significantly.”

Raymond believes that research in the latter area could make a difference, as the confined and complex environment means that cells can be extremely distorted. “Making the nuclei of these cells more rigid could prevent them from spreading,” Thereby limiting its tendency to metastasize.

Digital simulations performed by Rachele Allena. Despite the rigidity of the nucleus (red), cells can pass through microchannels with diameters of 12 microns (a) and 7 microns (b). In (c), the microchannel is only 2 microns in diameter and the nuclear laminin has been removed to reduce the rigidity of the nucleus and allow the cell to pass.

Rémond also believes that mechanical properties should also be incorporated into the study of biological digital twins. These model organs designed specifically for each patient are essential for the development of personalized medicine. They can help to better take into account the individual’s history, age and characteristics. These different options are still a long way from the clinical trial stage, but mechanobiology has already laid the foundation. “So far, mechanobiology has been mainly studied in vitro, and there is a need to develop in vivo approaches.” The Master concluded. “We still lack adaptable tools, but just as biochemistry revolutionized biology, our discipline will benefit from the emergence of scientists trained as pure biophysicists.” ♦

[ad_2]

Source link